Was the Novel Coronavirus Engineered? No Reason to Think So

Over the past weeks, I have been surprised to hear several scientists promote the hypothesis that the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, was engineered in a laboratory. I was immediately skeptical, as the identity of the supposed engineers always seemed to reflect individual politics: those with an anti-China bias blamed the Chinese, and those with an anti-American bias blamed the United States. Nevertheless, I endeavored to seek out any compelling arguments.

Some of the first evidence used to support the engineering hypothesis was the observation that some amino acids in the Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 match those in HIV-1, as explained in a preprint on bioRxiv. However, the manuscript has since been withdrawn. The main reason for the retraction was that it’s very common for different organisms to share modest (or high) similarities in nature, due to either chance or common ancestry. Indeed, as Laurie McGee points out in a bioRxiv comment, similarities between the original SARS and HIV were discussed in a paper in BMC Microbiology, published way back in 2003. But nobody concluded that SARS was engineered.

A similar argument has been made by Fang Chi-tai at National Taiwan University. The details are vague, but the reasoning seems to be that SARS-CoV-2 “has four more amino acids than other coronaviruses” and that this “is highly unlikely” to occur in nature. Elsewhere, Fang is reported to have said that “it is indeed possible that the amino acids were added to COVID-19 in the lab by humans”, that “the chances are very slim” the mutations occurred naturally, and again that “It is indeed possible that it is a man-made product.”

While we’re speaking of the possible, it’s also conceivable that all the world’s viruses are man-made, and that each of the world’s stoplights is operated by an invisible smurf. The fact that something is possible does not imply that it is likely.

The fact that something is possible does not imply that it is likely.

So, what convinced Fang that the engineering hypothesis is not only possible, but reasonably probable? To conclude that “such a large mutation” is “highly unlikely”, Fang presumably performed some calculations. Unfortunately, no details are given. The relevant calculations would have to consider what is known about RNA viruses, including (1) their very high mutation rate (10-6 to 10-3 per site per cell-infection); (2) the very high number of viruses per infected host (effective size of 104 virus copies per host); (3) their short epidemiological generation time (perhaps 4-7 days from host to host); and (4) the fact that coronaviruses are the largest of the RNA viruses (~30,000 nucleotide sites per genome) (Holmes et al. 2009).

As a very rough calculation, one might expect an average of (10-5 insertion mutations per site) × (30,000 sites) = 0.3 new mutations to occur every time a new coronavirus replicates. Some insertion events might involve 1 nucleotide; some 3 nucleotides (that is, a new amino acid); and some might even involve 12 nucleotides (4 new amino acids). As an approximation, let’s assume 4 events are necessary. Assuming a Poisson distribution, the probability of ≥4 mutations in a single virus is then P = 0.0003 (that is, 0.03% of the time). If one then considers that there are roughly 104 viruses per host, this implies that 0.03% of them — that is, 3 of them — will contain 4 or more mutations. Mutation clustering is a well-known phenomenon, so it’s entirely possible these mutations could be grouped together. Finally, suppose a very small number of hosts are infected, say 100 bats. Each of the bats might contain 3 virus copies with ≥4 mutations, for a total of 300 occurring in nature at any given time, with a brand new set of 300 produced every 4-7 days. This process then repeats, week after week, year after year. Eventually, just by chance, a set of 4 mutations will arise that allows the virus to better infect a new species, such as human. With enough time and enough human contact, novel viruses will jump the species barrier. At least, that has always been the explanation before — so what’s different this time?

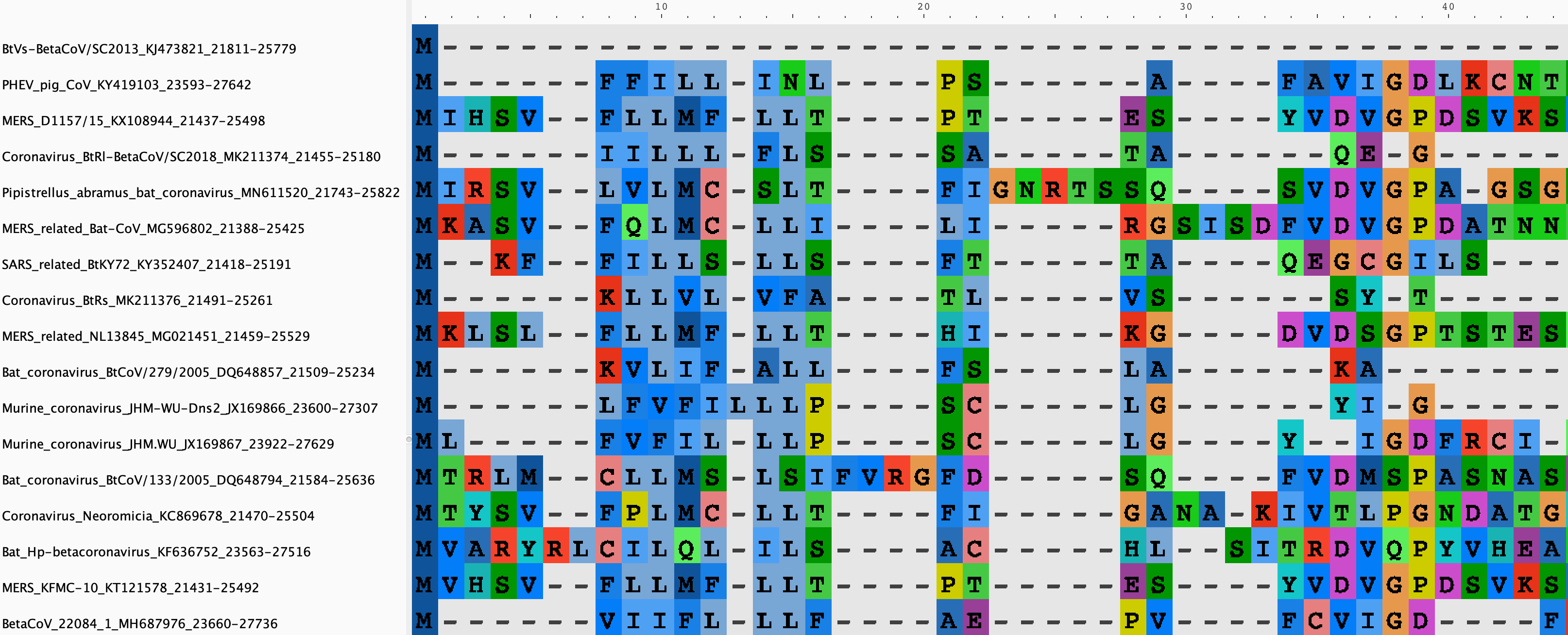

Although these quick calculations are better than nothing, they’re very rough. So, let’s examine some actual data. Specifically, shown below is an alignment of the first 44 amino acids of the Spike protein for a handful of related coronaviruses, including SARS and MERS (Zachary Ardern, personal communication; displayed using AliView):

The third sequence from the bottom has 2 unique amino acids (RL) at positions 6 and 7; the fifth sequence from the bottom has 4 amino acids (FVRG) at positions 17-20; the fifth sequence from the top has 5 unique amino acids (GNRTS) at positions 23-27; and so on. Clearly, it is very common for coronaviruses to acquire new amino acids in nature. Why not claim humans engineered them all? More specifically, to make the claim that the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 was engineered, surely we should require more evidence than vague statements that having “four more amino acids than other coronaviruses” is “highly unlikely” — unless we want to invoke a human hand in the emergence of all viruses.

To make the claim that the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 was engineered, surely we should require more evidence than vague statements that having “four more amino acids than other coronaviruses” is “highly unlikely” — unless we want to invoke a human hand in the emergence of all viruses.

It is not impossible for a virus to be genetically engineered in the laboratory. But extraordinary claims call for extraordinary evidence. At present, I am not convinced.

Reference

- Holmes EC. 2009. The Evolution and Emergence of RNA Viruses. New York: Oxford University Press.