The Role of HPV Gene E7 in Cervical Cancer

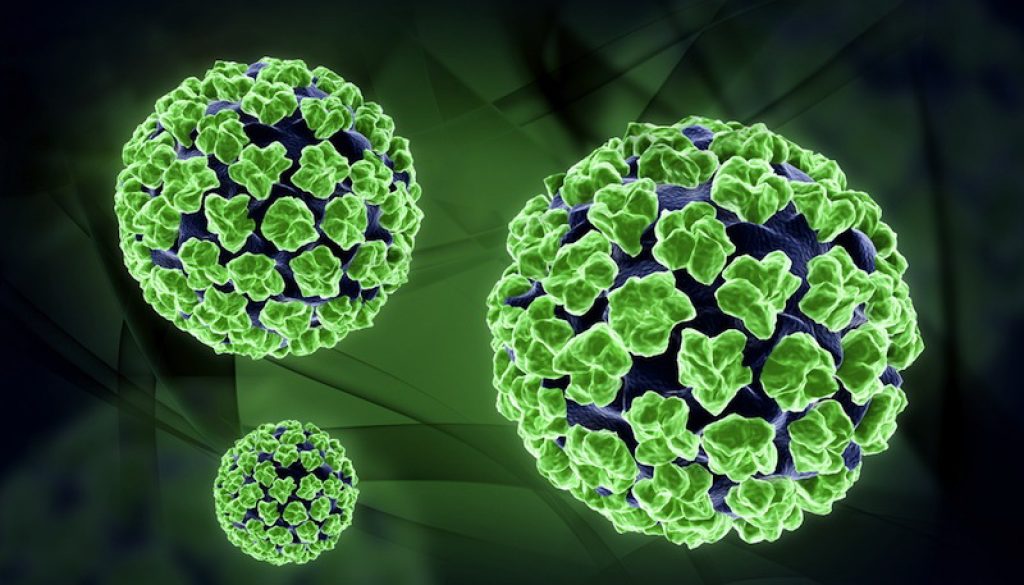

IMAGE courtesy of EstonianWorld.com

In a hard-fought paper appearing yesterday in Cell, colleagues and I show that the E7 gene of human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 displays marked differences between infections that are successfully defeated and those that go on to cause cervical cancer.

The E7 gene is one of two major cancer-causing genes in the HPV16 genome, and encodes a protein of only 98 amino acids. Even still, its protein must be expressed for cervical cancer to form. One of its primary roles is to bind and de-activate a protein called “retinoblastoma protein,” or pRB, which would normally cause cells to stop dividing when a problem is detected.

Put simply, our major finding is that, in cancerous HPV16 infections, the E7 gene is present in almost its exact original form—that is, very few to no mutations are present. On the other hand, the E7 copies found in benign infections—those that do not cause cancer, but are cleared by the immune system—are riddled with significantly more mutations, notably mutations that change the amino acids the gene encodes. This seems to be true in cancers from all over the planet, regardless of an infected individual’s ethnicity.

Why is this finding important? It suggests that maintaining E7’s near-exact sequence is necessary for HPV16 to cause cervical cancer. When the set of viruses infecting an individual cannot keep mutations from accumulating, these changes apparently destroy the cause of cervical cancer. We’re a long way from understanding how this works or how to act on this information, but my own take is that our own genetics are involved. Perhaps some humans have immune system genes that are able to target and destroy viruses carrying the cancer-causing copies of E7; in this case, the only surviving forms of the virus are those that don’t cause cancer. On the other hand, if the immune genes of other individuals don’t target E7 very well, and this cancer-causing form is the most effective at infection, these copies will be the ones to succeed—and, unfortunately, cause disease. Another possibility is that a special immune protein called APOBEC is able to cause mutations that deactivate E7.

To learn more, read the Cell press release, read the independent GenomeWeb press release, or go read the paper itself. And keep fighting for a cure!